Yeah I picked out this picture not for its relevance to astronomy but because it's really pretty and I want to go there. Let's take a field trip. This picture is of the Pic Du Midi observatory in the French Pyrenees. When you click the link that says Pic du Midi, it takes you to this really cool site where you can basically look around a semi tour thing that shows what the observatory looks like. It's actually pretty kickass, but kinda foggy and hard to see past the observatory deck and everything has like a foot of snow on it. The redish lights are manufactured lights from the La Montigie ski resort and from the urban parts of France and Spain. In the sky you can see Orion, Gemini, and a bright Mars (up at the top, not actually the normal orange color). The domes house amateur telescopes, a telescope used to help with the Apollo lunar landings, and the new sun watching CLIMSO (Christian Latouche IMageur SOlaire). The link they give you to CLIMSO is in French sooo yeah. Don't know much more than that.

Yeah I picked out this picture not for its relevance to astronomy but because it's really pretty and I want to go there. Let's take a field trip. This picture is of the Pic Du Midi observatory in the French Pyrenees. When you click the link that says Pic du Midi, it takes you to this really cool site where you can basically look around a semi tour thing that shows what the observatory looks like. It's actually pretty kickass, but kinda foggy and hard to see past the observatory deck and everything has like a foot of snow on it. The redish lights are manufactured lights from the La Montigie ski resort and from the urban parts of France and Spain. In the sky you can see Orion, Gemini, and a bright Mars (up at the top, not actually the normal orange color). The domes house amateur telescopes, a telescope used to help with the Apollo lunar landings, and the new sun watching CLIMSO (Christian Latouche IMageur SOlaire). The link they give you to CLIMSO is in French sooo yeah. Don't know much more than that.

Friday, January 25, 2008

Yeah I picked out this picture not for its relevance to astronomy but because it's really pretty and I want to go there. Let's take a field trip. This picture is of the Pic Du Midi observatory in the French Pyrenees. When you click the link that says Pic du Midi, it takes you to this really cool site where you can basically look around a semi tour thing that shows what the observatory looks like. It's actually pretty kickass, but kinda foggy and hard to see past the observatory deck and everything has like a foot of snow on it. The redish lights are manufactured lights from the La Montigie ski resort and from the urban parts of France and Spain. In the sky you can see Orion, Gemini, and a bright Mars (up at the top, not actually the normal orange color). The domes house amateur telescopes, a telescope used to help with the Apollo lunar landings, and the new sun watching CLIMSO (Christian Latouche IMageur SOlaire). The link they give you to CLIMSO is in French sooo yeah. Don't know much more than that.

Yeah I picked out this picture not for its relevance to astronomy but because it's really pretty and I want to go there. Let's take a field trip. This picture is of the Pic Du Midi observatory in the French Pyrenees. When you click the link that says Pic du Midi, it takes you to this really cool site where you can basically look around a semi tour thing that shows what the observatory looks like. It's actually pretty kickass, but kinda foggy and hard to see past the observatory deck and everything has like a foot of snow on it. The redish lights are manufactured lights from the La Montigie ski resort and from the urban parts of France and Spain. In the sky you can see Orion, Gemini, and a bright Mars (up at the top, not actually the normal orange color). The domes house amateur telescopes, a telescope used to help with the Apollo lunar landings, and the new sun watching CLIMSO (Christian Latouche IMageur SOlaire). The link they give you to CLIMSO is in French sooo yeah. Don't know much more than that.

Friday, January 18, 2008

3.2 APOD

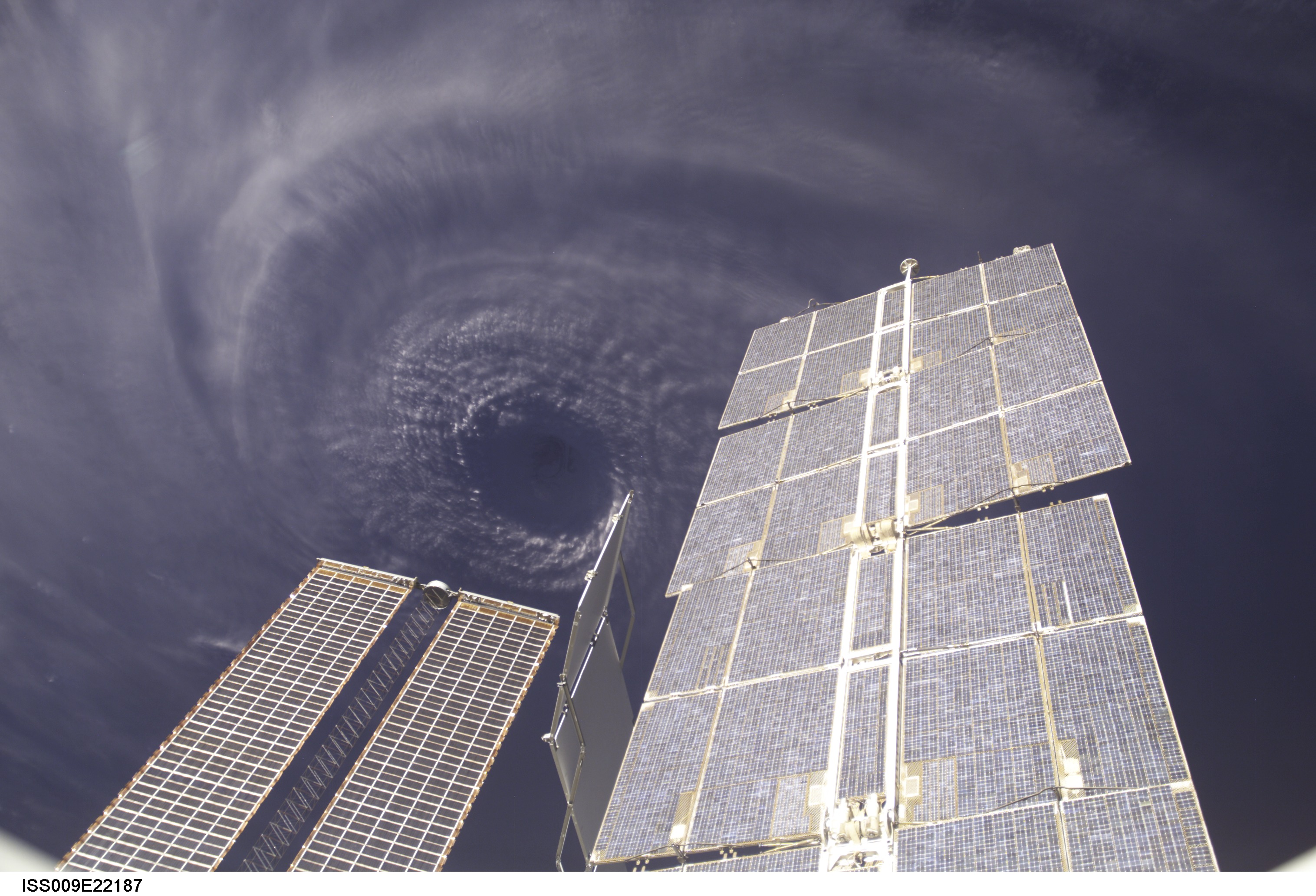

This picture of Hurricane Ivan on the eve of its power (it was a category 5 hurricane in 2004) was taken by the International Space Station. Ivan destroyed 90% of the houses on Grenada. Ivan's winds were greater than 200kmph which ranked it category 5 on the Simpson-Saffir scale, the common scale for hurricane ferocity. Ivan as a name for a hurricane has now been retired from Atlantic Ocean use by the World Meteorological Organization. Woot woot.

3.1 APOD

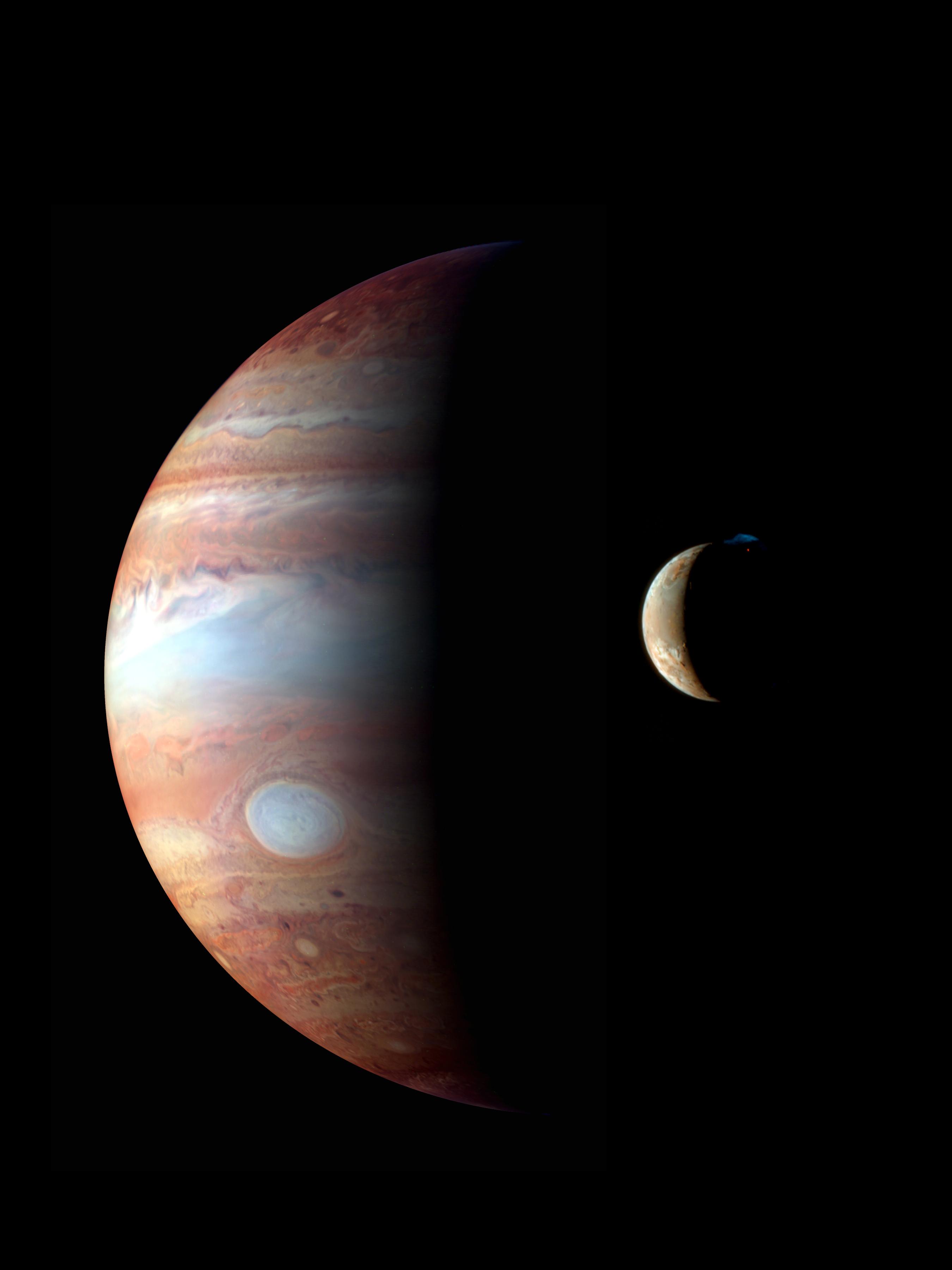

This montage was taken by the New Horizons spacecraft (scheduled to meet up with Pluto in 2015), which has been taking pictures of the planets as it heads towards Pluto. The picture of Jupiter was taken in the infrared, and as such the "great red spot" looks like a great white spot. Aside from the Great Red, other swirly circles appear on the planet, other hurricane type storms. If you look closely at Io (which was digitally superimposed on the picture... yay photoshop) you can see the volcanoe Tvashtar (discovered by the Galileo in 2001) erupting a blue plume. Red lava is apparent on the surface of the moon as well.

This montage was taken by the New Horizons spacecraft (scheduled to meet up with Pluto in 2015), which has been taking pictures of the planets as it heads towards Pluto. The picture of Jupiter was taken in the infrared, and as such the "great red spot" looks like a great white spot. Aside from the Great Red, other swirly circles appear on the planet, other hurricane type storms. If you look closely at Io (which was digitally superimposed on the picture... yay photoshop) you can see the volcanoe Tvashtar (discovered by the Galileo in 2001) erupting a blue plume. Red lava is apparent on the surface of the moon as well.

Thursday, January 10, 2008

Biography - Heinrich Olbers

Heinrich Wilhelm Matthaus Olbers was born in Arbergen, Germany on October 11 in 1758. He originally studied to become a doctor but built an observatory on the top floor of his home. Apparently blessed with the need for only four hours of sleep at night, he spent his days practicing medicine and his nights “relaxing” by studying the stars, comets, and asteroids.

Heinrich Olbers discovered a new way of calculating a cometary orbit. There were previous methods, but they were long and tedious and required many observations. Olbers basically figured out a way to expedite the process, by using observations from two different places on Earth. This method accurately predicted a comet with a seventy four year orbit (much like Halley’s comet) and was published under the title Ueber die leichteste und bequemste Methode die Bahn eines Cometen zu berechnen in 1797. Olbers discovered the asteroids Pallas and Vesta and suggested that the asteroid belt was actually the remains of a great planet that had been destroyed (the term ‘asteroid’ did not exist so the rocks were referred to as ‘minor planets’ and ‘planets’). He also discovered five comets (one of which now bears his name).

The Olbers paradox essentially states that if the universe is infinite and static (not expanding or contracting) with a uniform amount of stars populating it. The paradox was considered by earlier astronomers such as Kepler, Halley, and Cheseaux but is commonly attributed to Olbers. The paradox makes several important assumptions that basically define it: First, that brightness does not diminish with distance and so all stars should give off the same light regardless of distance (later found to be incorrect due to the inverse-square law); second, that no matter where you look in the sky your eye will see a star due to their numbers; and finally that give the first two assumptions, every point in the sky should be as bright as a star. So basically, the sky should be as bright during the night as it is during the day. So the paradox itself is the fact that the sky is dark at night. This was important because it meant that one of the assumptions was wrong. Astronomers of the 1950s and 60s decided that the paradox is also explained by the finite age of the galaxies, the finite speed of light, and the expansion of the universe (Olbers’ paradox has been used as evidence for the Big Bang theory). According to astrophysicist Paul Wesson in 1991, the reason for the night’s darkness has more to do with the age of the galaxies than with the expansion of the universe. The implications of Olbers’ paradox have interested astronomers for centuries.

Olbers assisted in the baptism of Napoleon II of France and died on March 2, 1840. Though he had contributed much to astronomy, he considered his greatest contribution to the scientific community to be helping another young astronomer gain renown.

Works Cited:

"Heinrich Olbers." Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1981.

"Heinrich Wilhelm MatthäUs Olbers." Wikipedia. 10 Jan. 2008.

"Science News: Vol. 139, No. 8, P. 125." JSTOR. 23 Feb. 1991. 10 Jan. 2008.

"Wilhelm Olbers." NNDB. 10 Jan. 2008

Heinrich Olbers discovered a new way of calculating a cometary orbit. There were previous methods, but they were long and tedious and required many observations. Olbers basically figured out a way to expedite the process, by using observations from two different places on Earth. This method accurately predicted a comet with a seventy four year orbit (much like Halley’s comet) and was published under the title Ueber die leichteste und bequemste Methode die Bahn eines Cometen zu berechnen in 1797. Olbers discovered the asteroids Pallas and Vesta and suggested that the asteroid belt was actually the remains of a great planet that had been destroyed (the term ‘asteroid’ did not exist so the rocks were referred to as ‘minor planets’ and ‘planets’). He also discovered five comets (one of which now bears his name).

The Olbers paradox essentially states that if the universe is infinite and static (not expanding or contracting) with a uniform amount of stars populating it. The paradox was considered by earlier astronomers such as Kepler, Halley, and Cheseaux but is commonly attributed to Olbers. The paradox makes several important assumptions that basically define it: First, that brightness does not diminish with distance and so all stars should give off the same light regardless of distance (later found to be incorrect due to the inverse-square law); second, that no matter where you look in the sky your eye will see a star due to their numbers; and finally that give the first two assumptions, every point in the sky should be as bright as a star. So basically, the sky should be as bright during the night as it is during the day. So the paradox itself is the fact that the sky is dark at night. This was important because it meant that one of the assumptions was wrong. Astronomers of the 1950s and 60s decided that the paradox is also explained by the finite age of the galaxies, the finite speed of light, and the expansion of the universe (Olbers’ paradox has been used as evidence for the Big Bang theory). According to astrophysicist Paul Wesson in 1991, the reason for the night’s darkness has more to do with the age of the galaxies than with the expansion of the universe. The implications of Olbers’ paradox have interested astronomers for centuries.

Olbers assisted in the baptism of Napoleon II of France and died on March 2, 1840. Though he had contributed much to astronomy, he considered his greatest contribution to the scientific community to be helping another young astronomer gain renown.

Works Cited:

"Heinrich Olbers." Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1981.

"Heinrich Wilhelm MatthäUs Olbers." Wikipedia. 10 Jan. 2008

"Science News: Vol. 139, No. 8, P. 125." JSTOR. 23 Feb. 1991. 10 Jan. 2008

"Wilhelm Olbers." NNDB. 10 Jan. 2008

Tuesday, January 8, 2008

Observation 1/3/08 - 1/4/08

Place: Cow Pasture at the end of Fruitville road

Temperature: 40 degrees or so

Time: 11 - 1

Weather: Slightly cloudy. Very cloudy at first, then it cleared up, clouds returned at the end

Stars: Sirius, Beetlejuice, Rigel

Constellations: Orion

We went specifically for a meteor shower. I saw 8 meteors. Two were bright - one was shorter and towards the west (I generally focused my sight around Mars and Orion, but this appeared out of the corner of my eye toward the Sarasota lights - a stray meteor?) and one was massive, originating in the Quadrens (spelling?) and shooting across the entire night sky (90 degrees?). Most were very small, not even as bright as a 1st or 2nd magnitude star. Length was shorter than the first digit of my thumb for some. I saw at least one other stray meteor near Orion, moving from east to west rather than North to South.

Temperature: 40 degrees or so

Time: 11 - 1

Weather: Slightly cloudy. Very cloudy at first, then it cleared up, clouds returned at the end

Stars: Sirius, Beetlejuice, Rigel

Constellations: Orion

We went specifically for a meteor shower. I saw 8 meteors. Two were bright - one was shorter and towards the west (I generally focused my sight around Mars and Orion, but this appeared out of the corner of my eye toward the Sarasota lights - a stray meteor?) and one was massive, originating in the Quadrens (spelling?) and shooting across the entire night sky (90 degrees?). Most were very small, not even as bright as a 1st or 2nd magnitude star. Length was shorter than the first digit of my thumb for some. I saw at least one other stray meteor near Orion, moving from east to west rather than North to South.

Friday, December 21, 2007

2.8 APOD

http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/0712/Mountains_spitzer_f.jpg

For picture go there ^^

This picture (W5) is close to constellation Casseopeia, picture taken in the infrared part of the spectrum by the most important infrared telescope: the Spitzer Space Telescope. The 'Mountain' was created by solar winds and hot radiation from a nearby star. The 'Mountains of Creation' are 10 times as large as the Pillars of Creation, captured by the Hubble Telescope. But the Pillars of Creation are prettier. Much, much prettier. W5 is a part of a 'complex region' called the Heart and Soul Nebula. The Heart and Soul Nebluae are basically just big red blobs. Not as pretty. This picture is 70 ly long.

For picture go there ^^

This picture (W5) is close to constellation Casseopeia, picture taken in the infrared part of the spectrum by the most important infrared telescope: the Spitzer Space Telescope. The 'Mountain' was created by solar winds and hot radiation from a nearby star. The 'Mountains of Creation' are 10 times as large as the Pillars of Creation, captured by the Hubble Telescope. But the Pillars of Creation are prettier. Much, much prettier. W5 is a part of a 'complex region' called the Heart and Soul Nebula. The Heart and Soul Nebluae are basically just big red blobs. Not as pretty. This picture is 70 ly long.

Friday, December 14, 2007

Observation at SCC

Day: December 7th

Place: SCC

Time: 7-9

Temperature: 60 ish degrees

We spent the earlier part of the night identifying constellations. The Summer Triangle was still vaguely in the sky to the West, but it fell as the night went on. We identified Polaris in order to get our bearings. We found Pisces by the circlet and momentarily confused Beetlejuice with Mars until Percy pointed out our mistake, which is what got us into the conversation of Orion's first magnitude stars. When Hannah came we re-identified the constellations we were familiar with, this time without help from Percy. One of the first things we looked at was the comet in Perseus. It was basically a big fuzz spot. I don't know that it could even be called white per say, it was just... fuzz. Once we had identified it in the binoculars, it was easy to see it without. We also looked at Subaru and the... hypeides? Spelling? The sister clusters. Due to Matt's request we looked at Uranus in the telescope, which was basically a blue dot and not overly exciting. Once Mars had risen over the treeline, we looked at it in the telescope and saw dark spots of continent sized formations on the planet. We also looked at M31 in Andromeda. The moon wasn't up.

Place: SCC

Time: 7-9

Temperature: 60 ish degrees

We spent the earlier part of the night identifying constellations. The Summer Triangle was still vaguely in the sky to the West, but it fell as the night went on. We identified Polaris in order to get our bearings. We found Pisces by the circlet and momentarily confused Beetlejuice with Mars until Percy pointed out our mistake, which is what got us into the conversation of Orion's first magnitude stars. When Hannah came we re-identified the constellations we were familiar with, this time without help from Percy. One of the first things we looked at was the comet in Perseus. It was basically a big fuzz spot. I don't know that it could even be called white per say, it was just... fuzz. Once we had identified it in the binoculars, it was easy to see it without. We also looked at Subaru and the... hypeides? Spelling? The sister clusters. Due to Matt's request we looked at Uranus in the telescope, which was basically a blue dot and not overly exciting. Once Mars had risen over the treeline, we looked at it in the telescope and saw dark spots of continent sized formations on the planet. We also looked at M31 in Andromeda. The moon wasn't up.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)